Be prepared for a lot of churn in late August as subscribers weigh up their Netflix, Disney, Paramount, fill-in-the-blank subscriptions against buying into Prime just to see the new Tolkein epic. And be prepared for the idiot-squad to tout this as evidence consumers have fallen out of love with the subscription model.

The New York Times ran a nonsensical post recently with the headline “Streaming Is Sadder Now” and the teaser “When Netflix and other companies face a loss of faith in the growth potential of streaming, we all will feel it.”

Across the publishing industry many of those opposed to the very notion of unlimited subscription in the book market are pointing gleefully to the not-quite-a-crisis unfolding in SVOD subscription as proof the model is flawed.

Fortunately that’s more wishful thinking than reality.

Yes, Netflix is losing subscribers, Netflix rivals are feeling the heat, and market growth predictions are being downgraded by the day.

The sky is falling!

But isn’t it always?

Of course, every industry loves a the-ski-is-falling headline in another industry to distract from the problems at home.

And let’s be in no doubt there are problems at home as a global recession sets in, supply chain issues abound, paper and ink prices spiral out of control, and an industry that spent the first months of 2022 wallowing in the glory of the 2021 publishing boom now comes to terms with a New Normal more aligned with the worst expectations of the Pandemic in mid-2020 than with the licence-to-print-money euphoria of New Year 2022.

But the focus of this post is to the analogies – if any – between SVOD and book streaming, a thought spurred by Carlo Carrenho on LinkedIn, who referenced the NYT article and asked, “Applicable to books?”

No, is the short answer, but that would make a short TNPS post indeed, while the long answer is too long for LinkedIn’s comment boxes, but fits rather snugly into the TNPS frame.

So let’s start with the key reasons why the SVOD market is currently facing difficulties, and let’s be clear from the onset that consumer disaffection with the subscription model per se is not among them.

Through 2020-21 video production took a hit as studios were closed by lockdowns. Major productions – not least Amazon’s The Lord of the Rings adaptation – were put on hold (this example only set for release in September).

Consumers gravitated to the subscription sites to occupy their enforced leisure time, but as the Pandemic eased there was not a commensurate return to the production and release schedule. A new-content hiatus lowered the appeal of the subscription price.

The new decade for the first time saw real competition in the SVOD arena, most notably with Netflix facing off Disney+, which had the advantage of owning key Netflix content (notably the Marvel franchises like Daredevil, Jessica Jones, Iron Fist, etc) which this year were taken from Netflix and put on Disney+.

But Disney+ was of course just one of a plethora of SVOD platforms that came into their own during the Pandemic video subscription boom, meaning competition was fierce at a level barely conceivable as the 2010s closed.

And along with that came the inevitable acceleration of exclusive content, notionally designed to attract and lock in new consumer interest but in reality hurting consumer interest as would be subscribers found that the term unlimited subscription increasingly lost meaning because subscription was limited to whatever content the particular service could offer.

Which means the current downturns being reported in subscriber numbers for Netflix, for example, is likely little to do with consumers no longer wanting to subscribe, but rather that they need to subscribe somewhere else to see the content they want.

If you want to see Disney and Marvel content you buy into Disney+. If you want to see Jack Reacher or The Lord of the Rings you spend your money at Amazon Prime. Be prepared for a lot of churn in late August as subscribers weigh up their Netflix, Disney, Paramount, fill-in-the-blank subscription against buying into Prime just to see the new Tolkein epic. And be prepared for the idiot-squad to tout this as evidence consumers have fallen out of love with the subscription model.

UPDATE 25 JULY 2022:

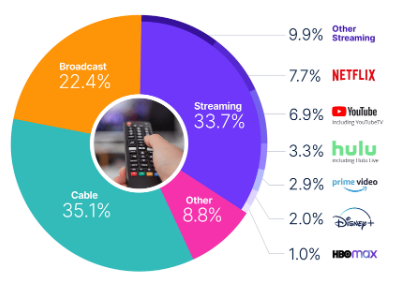

In late July comes affirmation of the TNPS analysis: streaming soared last month in the US, and is now a full on third of all TV consumption.

A shame the NYT hadn’t held back a few days with that nonsense post asserting streaming subscribers were in freefall.

Per the June stats, Netflix US streaming share is still bigger than Disney+ and Prime combined.

Add to all this the cold reality that there is a global recession underway (no need to wait for the economists to make it official – consumers are not stupid), and throw in the ongoing supply chain and transport problems (to which studio production is likely even more impacted than book publishers) and of course the ongoing and seemingly reinvigorated Pandemic, and it is hardly surprising the video subscription industry is in choppy waters.

Just as the publishing industry is. But you won’t find anyone in the publishing industry pointing to falling bricks & mortar retail sales and asserting the bookstore retail sector fad is over.

Book subscription? There really aren’t many valid comparisons. On the one hand we have the indisputable reality that most consumers love the unlimited subscription model, balanced against the equally indisputable reality that most mainstream publishers would rather stick pins in their eyes than give the model a fair chance.

This in turn warps the value of the few comparisons we can make.

In the audiobook market we are seeing, per Storytel and the non-English-language markets, a pattern emerging not dissimilar to that in the SVOD arena, where one of the main players has lately come up against serious challenges from rival players that did not meaningfully exist five years ago. Not just BookBeat and Nextory and the plethora of micro-players, but Audible embracing the unlimited subscription model.

Expansion here is now largely on hold following the Board coup at Storytel, with neither Audible, BookBeat nor Nextory showing any interest in global expansion beyond their current territorial reach.

Similarly subscriber numbers are not growing as fast as they once were, and in large part due to the same reasons explored above in relation to SVOD subscription.

In the core English-language audiobook markets, of course, the reality is there is no meaningful subscription, just the credit model, so no real comparison with SVOD streaming. Luddite resistance in the publishing industry means that will change only if/when Amazon is bold enough to force the unlimited model on the mainstream English-language publishers.

Given Audible is already unlimited as an option in six markets that time may not be too far distant.

In the ebook sector it’s a similar story. In the core English-language markets unlimited subscription is something mainstream publishers at best dabble around the edges of, notably keeping their feet dry when it comes to the – by far – largest player in the field, Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited.

We know from the pay-out to indie authors that this is a lucrative sector for those publishers who are on board, per this headline from TNPS:

Worth dwelling here briefly on the reality that while almost none of that $84 million came from unlimited subscription, we can safely say 100% of that $41 million came from unlimited subscription.

Now here, of course, there are sound reasons why publishers are unwilling to put even more of their eggs in the Amazon basket, but this doesn’t take away from the fact – and rather, perhaps, strengthens the case – that consumers are happily handing over their cash for unlimited subscription even without the big names to entice them.

We cannot say more because even the unlimited subscription services that do carry some meaningful mainstream content do not carry much, making the flat returns for publishers from unlimited book subscription a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Which brings us full circle to the headline. Streaming is sadder now only because market fragmentation and obsessive exclusivity of big-name content is making it so.

Even in a booming economic situation consumers will have only so many subscription packages they can afford, and in a recession the cruel reality of having to choose just one, or perhaps none, is impacting the market.

But it has nothing to do with consumer disaffection with the model.

Publishers would do well to try understand that and learn from the mistakes SVOD is making.

But of course it won’t, as we’ve seen lately with the spat between Storytel and BookBeat.

But no, there is no “loss of faith” in the growth potential of streaming, except among the quick-buck shareholder brigade that control far too much of both the SVOD and book streaming industries.

Just ask Jonas Tellander.