Digital formats (ebooks, e-journals, online subscriptions, learning management systems, etc) accounted for 70% of the total invoiced value of combined UK academic & professional book and journal sales

The US stats counter NPD PubTrack Digital doesn’t pretend to cover all ebook sales in the US, but covers most mainstream publishing output, while not having access to numbers from publishers like APub (Amazon publishing) and the sales from self-publishers, which collectively make up a sizeable chunk of the market.

The distinction is important for two reasons: first to be clear that the NPD numbers do not show anywhere near the full picture, and second that among those that do report to Nielsen, many have pursued a deliberate policy of raising ebook prices to depress demand and support the print sector.

With that in mind, the NPD Group’s latest numbers on April 2020, as lockdown closed off many avenues for print buying access, tell a story.

Unit ebook sales rose by almost a third in April, despite online print availability being largely unaffected.

For NPD PubTrack Digital, Kristen McLean says YOY trade ebook sales (as reported) fell 6 percent to 55 million unit sales, but April 2020 over March 2020 saw a 31% leap in reported ebook sales.

With brick-and-mortar retail bookstores shut down in the United States this spring the ebook format became more popular during the COVID-19 crisis. Ebooks are easy to purchase, can be read instantly after being downloaded, and eliminate any concerns over infection or availability.

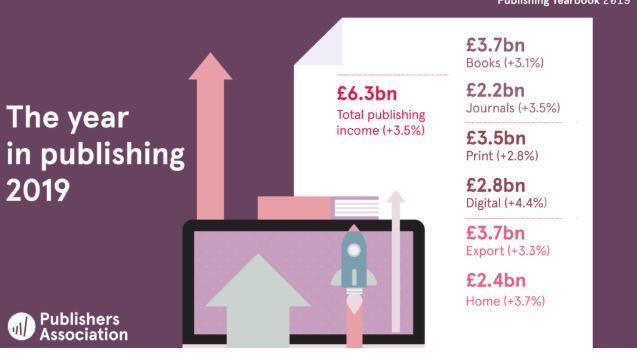

The statement is in stark contrast to the UK Publishers Association’s Stephen Lotinga who celebrated a report confirming 2019 to be UK publishing’s “best year ever” by playing down the fact that digital grew more than print last year.

The UK publishing economy in 2019 was worth an impressive £6.3 bn ($8 billion), made up of £3.5 bn ($4.45 bn) from print, up 2.8%, and a 4.4% rise to £2.8 bn ($3.56 bn) from digital.

That’s digital accounting for 44.5% of total UK sales last year. No wonder Lotinga was keen to stress how consumers prefer print.

There was, Lotinga explained, a

real desire and love for physical books (which are a) convenient format.

Lotinga added,

the ability to be able to pick up a book is something that is very welcome to a lot of people, especially when they spend their entire day looking at a screen, so it is a form of escapism.

In case that didn’t get the message across, Lotinga, a key proponent of “screen fatigue” as an alternative to blaming rising ebook prices for declining sales, continued,

Publishers have invested a lot into the covers and designs of books so that they look attractive and appealing in people’s homes.

There is something very special about gifting a book, particularly with children, which I think you don’t quite get in the same way as you would from a digital book.

Lotinga’s rant is an essay in jumbled thinking, simultaneously assuring us digital is something consumers don’t care for, while calling on the UK government to provide,

vital funding for schools and universities so they can buy the education resources that students need to learn remotely.

Of course fiction and non-fiction are separate segments of the market, but as the Nielsen US figures show, adult fiction ebook sales jumped 23% in April (over March), adult non-fiction ebook sales rose 36%, children’s non-fiction grew 39%, while children’s fiction jumped a remarkable 78% – all despite print still being readily available online.

And therein may lie a partial explanation – one Lotinga will find little comfort in – in that many regular bookstore consumers will have been forced online for the first time, and for the first time realise that they can not only buy their print books online and have them delivered to their door a day or so later, but that they can buy a digital version of the book and have it delivered to their device and be reading in seconds.

But let me shift gear here to take a closer look at the UK figures, which show a problematic scenario for Lotinga’s screen fatigue perspective.

For trade publishing the balance between print and digital is still quite stark.

• Print sales income was up 3.3% to £1.6bn.

• Digital (ebooks and audiobook downloads) sales income was up 4.6% to £336m.

In academic publishing the shift to digital is far clearer.

• Total sales income from academic & professional books and journals combined was up by 1.3%, to £3.3bn, this is 25.8% higher than 2015.

• Digital formats (ebooks, e-journals, online subscriptions, learning management systems, etc) accounted for 70% of the total invoiced value of combined academic & professional book and journal sales, up from 63% in 2015.

But hold on. Academic publishing is still very much a specialised arena where indie authors and commercial publishers like APub have little interest or impact. We can safely assume that while the PA figures for academic publishing won’t be the full picture, it will be close.

With trade publishing, by contrast, the numbers the PA uses are from Nielsen, but self-publishers and APub and other non-reported production plays a far bigger role, meaning that in the UK just like in the US, the UK numbers will show nowhere near the full picture.

Let’s take the PA value of £364 million for UK trade ebook sales by reporting publishers as an example.

We of course don’t know how much was brought in by non-reporting publishers and authors, but here’s some food for thought:

Amazon doesn’t break down its Kindle Unlimited subscription pot payout country by country, but we do know that in 2019 Amazon paid out a total of over $300 million in royalties to its KDP authors and publishers.

To be clear, the KDP pot goes to small presses and self-published authors enrolled in KDP Select. Not to the handful of bigger publishers participating or to big name authors like JK Rowling, or to APub authors, all of which get paid as if retail.

And of course this $300 million paid out in 2019 does not include a la cart retail sales on Amazon from those same self-publishers and small presses.

Nor does it include the unreported self-published and small-press revenue – and let’s be absolutely clear that that $300 million is royalties, not cold revenue – from other subscription services and other a la carte retailers.

Again, we cannot put a meaningful value on how much of that $300 million came from the UK, but we can say with absolute certainty that the $336 million value used in the Publishers Association Yearbook report is nowhere near the full picture.

The Publishers Association will have us believe digital accounted for less than 17% of trade revenue in 2019, while it accounted for 70% of academic publishing.

Safe to say we are nowhere near the 50-50 balance being seen in advanced digital markets like the Nordics, and so long as publishers continue to keep digital prices high to protect print that’s unlikely to happen.

But equally it’s safe to say the true figure for trade digital in the UK in 2019 will be significantly higher than the numbers we are given here by the UK Publishers Association.

2020 of course is a year unlike any other, but Lotinga and others will be quietly wondering and worrying if the surges in digital we have seen in the US, UK and globally during the Covid-19 lockdowns might mean that the new normal will leave a lot less room for attributing nuanced, lyrical and occasionally nonsensical (“a convenient format”) adoration of the printed book to a consuming public reacting to artificial price control to determine consumer format preferences.