It’s hard to remember now but there was a time, and not so very long ago, when music was a physically delivered product, with vinyl, magnetic tape or a CD the meaningful way for music publishers to make money from consumers.

When digital arrived as a possible alternative medium as this century unfurled (the iPod launched in 2001), and as a meaningful alternative with the arrival of the iPad in 2010 (the latter breathing new life into music video), there were all the usual doomsday predictions that nobody would ever pay for music again, streaming devalued music and artists, piracy would bankrupt studios and artists, the sky was falling…

Well, nothing new there. In publishing we’ve had all the same nonsensical debates, just a few years later than in music.

But with a decade of experience behind us now, has streaming devalued music, destroyed the industry, let the pirates take over, or otherwise caused the sky to fall?

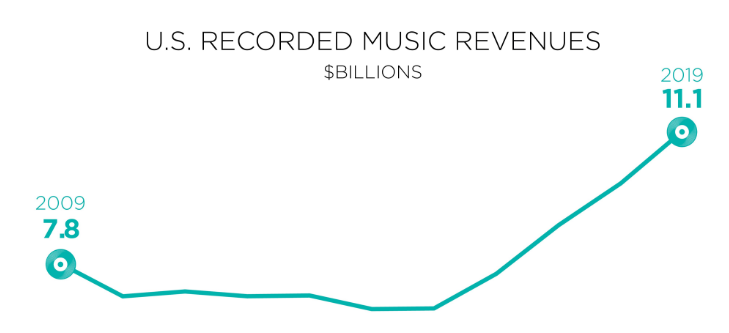

Well, they say a picture is worth a thousand words, so let this graph from Mitch Glazier, Chairman and CEO, RIAA, say it loud and clear.

Note that slippery slope from 2009 through to mid-decade, and then ask yourself what happened circa 2015-16 that suddenly not just reversed the decline but sent music revenue to hitherto unheard of heights?

Of course it was Spotify’s, Apple’s and Amazon’s unlimited streaming services (respectively 2011, 2015 and 2016). The slow start when Spotify arrived on the scene reflects initial music publisher resistance, just as we see today with book publishing.

But let’s return to Mitch Glazier:

Music isn’t “transitioning to digital”– it is leading a digital-first business.

Paid streaming services added an average of more than 1 million new subscriptions per month, as the total number of paid subscribers in the U.S. topped 60 million.

That growth didn’t “just happen.” First and foremost, it requires great music from amazing artists. Over the last decade, record labels have charted a path to new vitality and success by partnering with artists and licensing both established distributors and new start-ups to increase competition and choice.

And therein lies the value subscription brings: increased competition and choice.

In the pre-internet world your choice was only as good as your nearest music shop. Sure, you could order certain singles or albums, if you knew about them – and to know about them usually meant by chance hearing them on a niche radio station – but the reality was most consumers shopped from a small pool of content that bricks & mortar retailers and music publishers chose to offer.

That choice increased as online sales of vinyl, cassettes and CDs proliferated, but still it was a matter of handing over cold hard cash for what might be the only album you could afford that month.

In elementary economics terms, the opportunity was to buy the album you liked most and the opportunity cost was all that other content you couldn’t afford would stay out of your reach, and likely completely unknown.

That’s where subscription changed everything, by offering choice, affordability, and discoverability, and in doing so it fundamentally changed the consumer dynamic.

Music publishers were not instant in grasping the opportunity unfolding, but with fierce competition from major services like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, etc, all proving consumers wanted this new model, publisher resistance was futile, and music publishers learned to embrace and exploit the subscription opportunity. With spectacular results.

From TechCrunch this week:

Streaming music services’ share of total music revenues is bigger than ever. According to a year-end report from the RIAA, revenues from streaming services grew nearly 20% in 2019 to $8.8 billion, accounting for 79.5% of all recorded music revenues.

According to the RIAA, the U.S. streaming market in 2019 was larger than the entire U.S. recorded music market just two years ago.

In addition, revenues from recorded music in 2019 grew 13%, from $9.8 billion to $11.1 billion (retail). This represents the fourth year in a row of double-digit growth, which the RIAA attributes to increases from paid subscription services.

At which point, let’s take a step back and ask ourselves honestly why this is not happening in publishing.

And the honest answer is, it is. In the Nordics.

In the USA? Not so much.

But the reason is not that US consumers are indifferent to subscription’s charms, as the music and video industries show. But with subscription in publishing there’s the elephant in the room we need to mention. Amazon.

For reasons beyond the scope of this essay Amazon was late to the music subscription game and still takes second place to Apple, although the gap is narrowing.

Had Amazon managed to dominate digital music in the way it has digital books, things might have been very different. But music publishers do not have the same love-hate relationship with Amazon that book publishers do and that has allowed music publishers to overcome their reservations about subscription and embrace the new opportunities subscription brings.

For the US and UK markets at least, it’s unlikely we’ll see book publishers rise to the subscription opportunity in the same way we have in the Nordics.

But elsewhere in the world, most of which is beyond the interest of Amazons digital publishing ambitions…

…we can expect to see digital subscription become the powerhouse of the global books industry in the same way it has for music.

Interesting article. Helps to clarify a conversation I’ve been hearing more often lately around the subscription model. I’m still curious to know where all that extra revenue is going in the music industry. As a whole, the revenue has increased since 2009 thanks to subscription models—but has that increase translated into a corresponding increase in revenue for artists (in this case, musicians)? Or is it being siphoned by other members of the music publishing chain (labels, subscription platform, etc.)? I’m not so sure subscription models are ultimately more beneficial for the content creators than the old physically delivered product. I’d be curious to see what share of the pie the artist gets once everyone else along the way has taken their slice. I’m genuinely curious. If you have any info to pass on regarding this, I’d be delighted to read it.

There are concerns that some artists are not receiving a fair share, but as ever we need to be wary of such claims. As with books, streaming rewards volume. For an artist or author seeing downloads in small numbers it’s likely the a la carte model would give them a better rate per download. But would they be reaching these new audiences at all? For artists and authors with volume interest it would seem they are raking in big cash.

Kindle Unlimited, the Amazon unlimited subscription service is perhaps a good example. Many authors say their income dropped, yet KU paid out over $300 million last year to its KU authors, and plenty of authors are rolling in serious cash from KU.

As with any model, there are many hands taking a cut. That’s business.

The value of subscription for artists and authors lies in being affordable, accessible and discoverable. The challenge for publishers is balancing what subscription can deliver against what they have invested in the traditional model that might be cannibalised.

For approximate stream payouts, this post from January 2020 is instructive.

https://www.dittomusic.com/blog/how-much-do-music-streaming-services-pay-musicians

To which I’d add the “long tale” factor. When you sell a single download a la carte for say $5 then no matter how many gazillion times that download is replayed you won’t see a cent more. The a la carte download might get 500 plays in week 1, 200 in week 4 and only handful thereafter. No more money coming in. Who will pay in five years time to buy that backlist title? With subscription if the music lover returns to the download you get paid every time. And it might be picked up by an untold number of new music lovers who would never pay $5 but will happily play it over and over since it’s costimn them nothing extra, but every play clocks up revenue for the artist.