This is a vast continent of 54 countries and more languages than you can begin to count. And a rich, diverse and incredibly vibrant storytelling tradition that is finding its way into books, comics, television, film, webtoon and theatre, yet that is often unseen and unheard by the wider world.

While much of the world looks the other way, many African publishers are now embracing the digital opportunity, leveraging post-colonial technology to liberate the continent’s publishing agenda from legacy print-focussed publishing ideology.

With 1.4 billion people, over 600 million of whom are online, digital offers Africa’s publishers a nearly level playing field to reach audiences at home, across the continent and around the world.

This past week some thirty publishing professionals across Africa (Côte d’Ivoire, Mali, Togo, Benin, Cameroon, Ghana, Senegal and Madagascar, plus France) connected online to discuss the Literary Prizes in Africa.

Agnès Debiage led the event from the Côte d’Ivoire capital, Abidjan, as part of a professional component partnership between the Abidjan International Book Fair and the Salon du Livre Africain de Paris.

A second event is scheduled for mid-December, focussed on rights.

The countries participating, per list above, show a sub-Saharan francophone base centred on West Africa, with Madagascar a geographical outlier, and Ghana a language outlier (Cameroon has both French and English as national languages), perhaps reflective of the industry base Agnès Debiage works in.

But it will be interesting to see how this expands to include the wider continent, and how much inter-connectivity we might see between the various publishing quarters across the continent, for so long divided along historic, linguistic and racial grounds.

YouScribe has done much to bring francophone Arab and sub-Saharan Africa to the digital table, and of course the Sharjah Book Authority | هيئة الشارقة للكتاب has been instrumental in giving sub-Saharan and North African publishers a voice at the Sharjah International Book Fair. Check out this summary by Emma House for Publishers Weekly for the 2023 event

Recently, eKitabu opened up the digital publishing game with its ground-breaking professional days event at the Nairobi International Book Fair in Kenya.

And in Algeria, the latest Algiers International Book Fair embraced the whole continent in a way not seen hitherto, which perhaps helped it achieve its record-breaking 2.7 million turnout.

Debiage herself frequently is present at and reports on the many African publishing events that (as with Algiers) don’t make the western trade press (Morocco’s children’s book fair, for example, or this from Mauritius, or this from Benin).

But this is a vast continent of 54 countries and more languages than you can begin to count. And a rich, diverse and incredibly vibrant storytelling tradition that is finding its way into books, comics, television, film, webtoon and theatre, yet that is often unseen and unheard by the wider world.

A wider world where only a handful of African literary names are known, and where instead we see African’s beautiful cultures parodied and squeezed into western-friendly stereotype packages like The Lion King, where the voices of anthropomorphised animals count for more than human voices.

In the world of legacy print publishing it’s a sad truism that it is often easier for someone in Africa to buy the latest book from an American or European author than from an author in a neighbouring African country, and the supply-chain woes that are impacting the entire world right now can only make that problem worse.

At which point let me digress slightly from the bigger picture to share some personal experience.

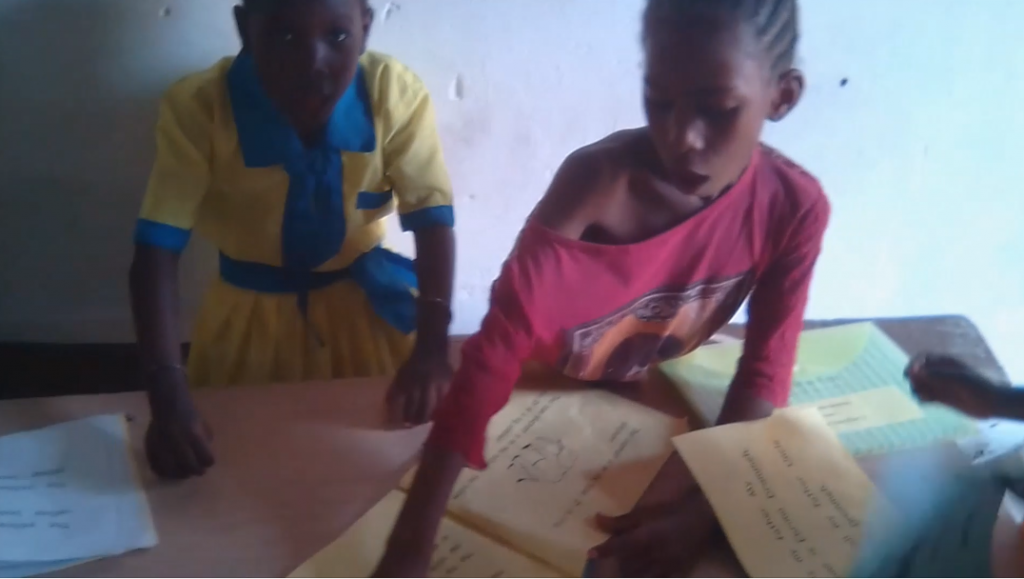

I’m writing this beneath picture-postcard blue skies in West Africa’s The Gambia, where I run a school where every day we tell the children to be proud to be Gambian, to be proud to be African, to be proud to be black. But apart from a handful of government-produced school textbooks for primary schools (published outside the country) there is almost no literature available for children other than what comes into the country via tourists’ donations, and which invariably depicts white children in Europe or America, or at best black children doing European and American things in European and American settings.

Elsewhere on the continent there is some exciting children’s literature being published, but getting access to it at affordable prices here is a triumph of hope over experience. That’s not to say Kenyan or Ghanaian or Nigerian children (for example) especially share languages and culture (other than the English being taught at school) with those in The Gambia, but it’s a step in the right direction. The children depicted are at least African.

With fewer than 3 million people, the publishing challenges here in The Gambia are exceptional. Immediate neighbouring countries (in fact, there’s only one!) publish in French, so importing books across the border is no solution.

The consequence is an appalling literacy rate in The Gambia (17th from bottom in the world), where few children speak or read good English (which, love it or hate it, is an international language they need to know) and almost no-one can read in local languages even if books were published.

My school is an exception. Ever child can read, because I’m able to write and desk-publish reading material for them as they need it.

But my A4 stapled pages of print, while very successful in getting children reading, are a far cry from a “real” book.

Last year we received a donation of books from BIG BAD WOLF BOOKS [BBW BOOKS] (Thanks, Geetha Nair!). For many of the nursery school children (nursery school here is age 3-6) it was the first time they had ever seen a “real” colour-printed book with glossy pages and hard covers.

In that respect The Gambia fits the worst stereotypical images of poverty-stricken Africa, a world apart from our comfortable western lifestyle. But other parts of Africa are every bit as advanced as Europe or America. Except, it seems, when it comes to the publishing industry.

Digital is far from an instant panacea, but it can and will help level the playing field.

But Amazon’s Kindle store is widely unavailable across the continent, Apple has no Apple books store in Africa, and Google Play Books is only in two countries out of fifty-four.

And even where a North American digital books player is available (Kobo, for example), the prices are set in US dollars at US values, and in any case anachronistic territorial rights rules mean much content is unavailable even if we have the means to pay.

It’s another sad truism that many African publishers that do have digital versions are more likely to be selling those titles outside Africa than within, because the digital retail and delivery infrastructure is simply not developed enough to sustain pan-African reach.

That’s changing. Fast. YouScribe has over 1 million subscribers across the continent, showing that the interest is there and that the model can work. Ama Dadson‘s AkooBooks Audio is leading the way in upper-sub-Saharan Africa in making digital audio a thing, and in Egypt Ali Abdel-moneim is alongside Storytel Arabia ensuring digital audio reach expands across North Africa.

There are plenty more examples, and there’s much to be excited about as African publishing evolves, and AI perhaps holds the most promise, especially as and when AI reaches the point where it can operate effectively with indigenous African and global languages.

But still intercontinental rivalries, exacerbated by historic legacy, by language, by race and by nationalist sentiments, cast a shadow over Africa’s publishing potential.

And the widely-held fixation on legacy publishing models and formats, whether consciously (“a book is not a book unless its ink on paper“) or through indifference to or ignorance of what is evolving in the global publishing industries, or indifference to or ignorance of just how many people are online in Africa as we head into 2024, prevents African publishing taking its rightful place at the global publishing table.

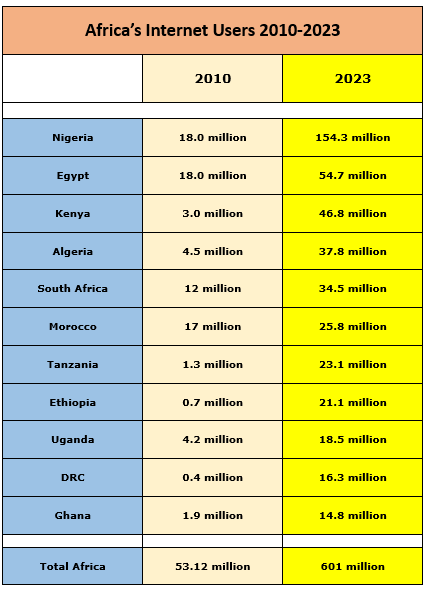

I’ll end this post by once again tackling that last point, with the TNPS 2023 African digital reach chart, which shows the top internet-active African countries with their numbers of internet users in 2010 juxtaposed with the 2020s numbers.

In 2010 there were just 53 million people online across the entire African continent. Today Egypt alone has more internet users than that. And Kenya is not far behind, up from 3 million internet users in 2010 to almost 47 million today. Nigeria has 154 million internet users

To put that in context, Nigeria has more people online than Germany and the UK combined. Egypt has as many people online as Italy. Kenya has more people online than Spain. Algeria has more people online than Canada. Morocco has more people online than Australia, and Tanzania has as many people online as Australia. Ethiopia has twice as many people online as the digital publishing powerhouse that is Sweden.

All told, there are over 600 million Africans online as we close 2023. That’s more than South America and the Caribbean combined. That’s 200 million more internet users in Africa than in the European Union. That’s almost literally twice as many people online in Africa as there are in the world’s biggest book market, the United States.

And Africa is still only at 43% internet penetration. Not even halfway to reaching its potential.

Around the world a total of 5.4 billion people have a device in their hands that, by definition, could be used for reading African ebooks, listening to African audiobooks, reading African literature online, and bringing global revenue and recognition to African publishers and African authors.