Just how many music, film and other subscription services are authors and publishers using daily in their personal lives while simultaneously insisting consumers will not have that option for books?

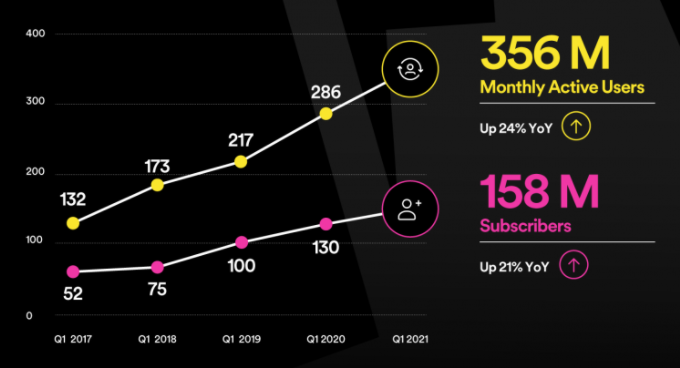

With 158 million monthly paying subscribers and 356 million monthly average users the once music-only but now all-things-audio subscription platform Spotify continues to lead the subscription sounds arena globally. And by globally we are talking across 178 countries.

Safe to say music made up the bulk of those numbers, but podcasts and more recently audiobooks are now making their mark among Spotify consumers, and what matters to publishing is not where things are today but what this portends for the future.

First a quick look at the recent trajectory, via this graphic from the latest Spotify press release. From 52 million subscribers in Q1 2017 to 158 million in 2021.

Next a look back at an essay from Spotify founder and CEO Daniel Ek who just last month laid out his thoughts on the economics of streaming.

Ek:

Since its 2014 low, the music industry has grown by 44%, driven primarily by streaming revenues, which increased 500% over this same period.

At which point let me interrupt Ek to add a headline from TNPS back in February 2020, back in the heady days before the pandemic became a pandemic, when digital was still a sideshow for the publishing industry.

In USA 80% of music revenue came from streaming as the market grew, with 2019 streaming alone bigger than total market revenue in 2017.

I said then:

It’s hard to remember now but there was a time, and not so very long ago, when music was a physically delivered product, with vinyl, magnetic tape or a CD the meaningful way for music publishers to make money from consumers.

When digital arrived as a possible alternative medium as this century unfurled (the iPod launched in 2001), and as a meaningful alternative with the arrival of the iPad in 2010 (the latter breathing new life into music video), there were all the usual doomsday predictions that nobody would ever pay for music again, streaming devalued music and artists, piracy would bankrupt studios and artists, the sky was falling…

Well, nothing new there. In publishing we’ve had all the same nonsensical debates, just a few years later than in music.

But with a decade of experience behind us now, has streaming devalued music, destroyed the industry, let the pirates take over, or otherwise caused the sky to fall?

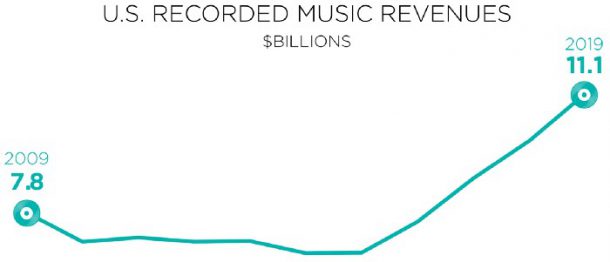

Well, they say a picture is worth a thousand words, so let this graph from Mitch Glazier, Chairman and CEO, RIAA, say it loud and clear.

Note that slippery slope from 2009 through to mid-decade, and then ask yourself what happened that suddenly not just reversed the decline but sent music revenue to hitherto unheard of heights?

Of course it was Spotify’s, Apple’s, Amazon’s and Deezer’s unlimited streaming services (respectively 2011, 2015, 2016 and 2016). The slow start when Spotify arrived on the scene reflects initial music publisher resistance, just as we see today with book publishing.

At which point I quoted Mitch Glazier of the RIAA:

Music isn’t “transitioning to digital”– it is leading a digital-first business.

Paid streaming services added (in 2019) an average of more than 1 million new subscriptions per month, as the total number of paid subscribers in the U.S. topped 60 million.

That growth didn’t “just happen.” First and foremost, it requires great music from amazing artists. Over the last decade, record labels have charted a path to new vitality and success by partnering with artists and licensing both established distributors and new start-ups to increase competition and choice.

And therein, I said, lies the value subscription brings: increased competition and choice.

In the pre-internet world your choice was only as good as your nearest music shop. Sure, you could order certain singles or albums, if you knew about them – and to know about them usually meant by chance hearing them on a niche radio station – but the reality was most consumers shopped from a small pool of content that bricks & mortar retailers and music publishers chose to offer.

That choice increased as online sales of vinyl, cassettes and CDs proliferated, but still it was a matter of handing over cold hard cash for what might be the only album you could afford that month.

In elementary economics terms, the opportunity was to buy the album you liked most and the opportunity cost was all that other content you couldn’t afford would stay out of your reach, and likely completely unknown.

That’s where subscription changed everything, by offering choice, affordability, and discoverability, and in doing so it fundamentally changed the consumer dynamic.

Music publishers were not instant in grasping the opportunity unfolding, as we see from the graph, but with fierce competition from major services like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Deezer, etc, all proving consumers wanted this new model, publisher resistance was futile, and music publishers learned to embrace and exploit the subscription opportunity. With spectacular results.

Spotify’s consumer-base of proven unlimited-subscription fans is going to turn heads, for sure. Publishers know in their hearts that letting Audible have control of the audiobook market is going to backfire one day.

And they also know that the Audible model of one credit per month subscription has its downsides. Not least that the unlimited subscription model is far more attractive to consumers.

They also know that the unlimited model opens up backlist revenue opportunities like no other.

That’s not so important right now, when publishers are still catching up with audio for their frontlist titles. But the time is not that far off where mature-market publishers are going to look again at the unlimited model, grasp that revenue and profit are not the same thing and that big revenue with less profit isn’t such a great idea, and start switching allegiance. This is business, after all, and money talks.

So let’s talk money. Or rather, let’s return to Spotify CEO Daniel Ek to talk money:

Still, artists ask me all the time why they’re not making more money. If the music industry is generating so much, then where the hell is it going? These are fair questions. So, we’re launching a new site, Loud & Clear, to increase transparency and shed light on the complicated economics of music streaming.

Streaming is thriving and has been key to helping more artists find a global audience. There are more artists than ever before. That’s awesome. It means new genres, more music crossing borders, and more artists finding new fans. It also means new artists joining Spotify every day, along with the entire history of music that came before them. More artists want to share their art, reach fans and earn a living from music. And it’s happening.

From streaming on Spotify alone, we’re seeing growth from artists at all stages of their career:

since 2017, the number of artists generating

more than $50K/yr is up 80%;

more than $100K/yr is up 85%;

and more than $1M/year is up 90%.

Today, 57K artists now represent 90% of monthly streams on Spotify — a number that has quadrupled in just six years. This means that the number of the most listened to artists in the world is growing and more diverse.

Ek concluded:

Our goal is to help musicians that aspire to be, or are professional to make a living. It’s something we take seriously every day. Of course not every one of the millions of artists on Spotify have found the same success. That will never be true. Fans will ultimately decide who succeeds and thrives, but our focus remains clear: Continue to create more opportunities for more artists to reach more fans.

What, exactly, do book publishers find so difficult to understand there? More authors reaching more readers ought to be the holy grail of publishing, but book publishing is still in that early-2010s rut that music found itself in, unwilling to even think, let alone step, outside the comfort zone that is how things have always been done.

Yes, in the mature markets book publishing has not seen the disturbing downward spiral that hit music in the early 2010s, and panic over the pandemic has given way to unstated euphoria as book publishers learned bricks & mortar bookstores aren’t as indispensable to publishing’s bottom line as was first believed.

But publishers mostly still live in a 2010s world where the domestic markets mean existing customers have to be squabbled over for market share (the pandemic showed that actually there’s plenty of room for growth) and export markets meant a handful of countries that were commercially viable to export printed books to in the last century when territorial rights were carved up and, it seems, are now set in stone in many publishers’ minds.

While digital books subscription has evolved this past decade the English-language market perception of opportunities has been warped by the dominance of Amazon’s Kindle Unlimited subscription service (which larger publishers tended to steer clear of and where indie authors are obliged to go exclusive to participate) and Amazon’s Audible (which with its one-monthly-credit system doesn’t really qualify as meaningful subscription, just a monthly retail commitment).

In the wider markets the Scandinavian experiment where three Swedish platforms have taken the region (and beyond) by storm is still primarily an audiobook affair (because of the way the Swedish digital books market evolved), although ebooks are emerging a strong player.

As we begin to (hopefully) leave behind the worst of the pandemic (it’s unlikely we’ll ever see the back of it, and there are no guarantees at this stage it will not return with a vengeance to the countries currently seeing real progress) the question of subscription needs to be faced up to by publishers across the board.

Because subscription is what consumers want, and at the end of the day businesses that serve consumers will either adjust their business model to meet new consumer needs, or perish.

Author and publishers who hide behind faux arguments about subscription need to ask themselves two things:

First, how is it other media like music and film are not just managing but embracing the subscription model?

And second, and perhaps most importantly, just how many music, film and other subscription services are authors and publishers using daily in their personal lives while simultaneously insisting consumers will not have that option for books?