The reality is consumers want content when they want it, how they want it, and at a price they are comfortable with.

Cobbling together the latest stats during an internet meltdown – as was the case back in February when this post originally aired – is a recipe for conservative guestimates, and my best numbers for digital subscription globally were, it seems, woefully conservative.

But fast forward just a month and news from the USA’s Motion Picture Association that global video streaming subscriptions surpassed 1.1 billion in 2020.

That’s just video, not news or music, ebooks or audiobooks or podcasts.

At which point time to dust off the key elements of the February post once more.

~ ~ ~

The more I write about publishers gingerly dancing around the subscription topic the more it seems like superstitious thespians calling Macbeth “the Scottish play” or the characters in Harry Potter that dare not speak the name of the arch-villain Voldermort.

In some ways it’s reminiscent of that rubbernecking-a-multi-vehicle-car-crash moment in 2007 as the Amazon Kindle store launched in the USA, when publishers realised with a mixture of horror, fascination and disbelief that they weren’t bystanders, but were passengers in the vehicles.

Many publishers have spent the years since trying to juggle the reality that ebooks had arrived with the fantasy that publishing could just carry on as it had in previous decades.

And those same publishers have watched with mounting horror as the natural evolution of the ebook and digital audiobook morphed into the subscription model, necessitating a new juggling act where publishers watched the music, news and video industries transition to subscription while simultaneously doing their best to ensure publishing subscription start-ups did not gain traction, and silently cursing those crazy Swedes who weren’t onside and were irresponsibly embracing the model and showing how successful it could be.

Which (brought) us to this post about advertising and subscription news.

We already knew that data from the Advertising Association and the World Advertising Research Center had shown digital ad revenue in the news publishing sector had doubled in value between 2011 and 2019, while print ad revenue plummeted, and of course that the 2020 pandemic accelerated that shift.

But per the (at the time) latest from the news-publishing trade journal, What’s New In Publishing, quoting WARC’s Rob Clapp,

It is digital subscriptions that have generated the most attention as a way of countering the decline in print advertising revenue. For publishers, the coronavirus-induced growth in digital audiences appears to have lasted beyond the initial outbreak.

Of course news publishing and book publishing are different animals, just as are music or TV and film. But this is not the twentieth century. We live in an interconnected, trans-media world where no publisher is an island, and more importantly no consumer is immune from subscription’s charms.

(A week previously) What’s New In Publishing (had) reported that,

53% of (UK) digital publishers witnessed positive revenue growth in Q3 2020, boosted by a significant rise in subscription revenue.

WNIP led with the sub-header.

The shift to subscription revenue has gained serious momentum.

To which we might add, broadening this debate out to encompass video, a mention of DisneyPlus, which recently reported that it started 2021 with 94.9 million subscribers, all acquired in just 14 months. The company had originally aspired to reach 100 million subscribers over four years.

Needless to say Disney is now rapidly revising its digital subscription plans and the model will take centre stage in the company’s operations.

Yes, Disney is Disney. But this is a pattern, not an outlier book publishers can just laugh off.

Spotify, best known for music, but lately also into podcasts, and now entering the audiobook arena, started 2021 with 155 million paying subscribers.

HBO and HBO Max are fielding over 60 million global subscribers, with parent company AT&T CEO John Stankey stating,

The release of Wonder Woman 1984 helped drive our domestic (US) HBO Max and HBO subscribers to more than 41 million, a full two years faster than our initial forecast.

Netflix is of course the big daddy of the subscription world, starting 2021 with over 200 million subscribers.

But more significant still is where these giants are likely to be in five years time.

Digital TV Research projections expect Disney Plus to hit 294 million subscribers in 2026, exceeding Netflix, which is expected to have “only” 286 million subscribers. In revenue terms Netflix will still have the edge, with a forecast of $39.52 billion in revenue in 2026 compared to a mere $20.76 billion for Disney Plus.

The projections also put Amazon Prime Video on target for 184 million subscribers (it was at 150 million in early 2020), and HBO for 50 million.

Amazon’s numbers are of course part of a bigger non-video offering, so not so easy to shuffle into the video equation, but unquestionably subscription.

And then there’s Amazon Music, to which we can add another 55 million subscribers to the list. And 68 million subscribers to Apple Music.

The above-mentioned list of course focuses on the western media giants, but in global terms we then need to acknowledge the existence of a plethora of other subscription offerings out there that we in the west may never have heard of but that are the mainstay of subscription viewing and listening globally.

Per a report in The Motley Fool, total global music subscription alone amounted to 358 million.

That will include Tencent’s 40 million paying subscribers and Google’s ever-growing subscriber base among many.

Video? In addition to the aforementioned players, YouTube was fielding 20 million paying subscribers in early 2020, and we’re still nowhere near covering everything.

From Rapid TV News:

The 20 countries in the Middle East and North Africa region are set to have 32.65 million subscription video-on-demand (SVOD) customers by 2026, up from the 14.16 million recorded at end-2020 says a study from Digital TV Research.

Repeat across Latin America, Asia, Oceania and Africa.

A report in September 2020 told that the Asia-pacific region is forecast to reach 467 million video subscribers by 2025.

Again allowing that many may be multiple subscriptions by one subscriber, even so it’s hard not to envisage more than a billion people around the world using the subscription model by 2023.

And that may be conservative. One report suggested that India alone might have 500 million video subscribers by 2023. If that sounds implausible, keep in mind that India started 2020 with 560 million people online. It started 2021 with 749 million people online, and that three quarters of a billion internet users still puts India at only 54% internet penetration.

But let’s return to the UK as we start to wind down this post, with a report in Rapid TV News that,

More than 4/5 of UK turned to streaming during lockdown.

Per Rapid TV News,

The survey found that in general consumers regarded streaming services as delivering on their content needs. 70% of UK consumers that have streaming subscriptions said that they get all of the content that they need from services.

Yet nearly three-quarters (73%) said they would prefer to pay a lower price for a subscription package that had less content overall, but the content they got was more tailored to their preferences. TV/streaming viewers were most in favour of a more restricted but personalised subscription.

When asked what drives loyalty to a subscription service in general, more consumers cared about the quality and quantity of content available to them, rather than price. Just under half (46%) of consumers said the quantity of content factors into their loyalty to a service, while content quality was indicated by slightly fewer (44%). Just 29% said price or availability of different pricing options.

Lots of lessons there for book publishers, but the big question is at what point do we stop pretending book publishing is a special case and book consumers don’t care for the streaming model, and acknowledge the reality of the sea-change in the way consumers consume content.

We saw in 2020 how film production companies desperately clinging to the old model of theatre-first releases were shown to be at odds with consumer demand when the pandemic forced streaming-first or streaming-simultaneous releases on an unsuspecting world. Now Hollywood is rethinking its strategies.

Warner Bros plans to release all its 2021 catalogue simultaneously in theatres and on streaming platforms.

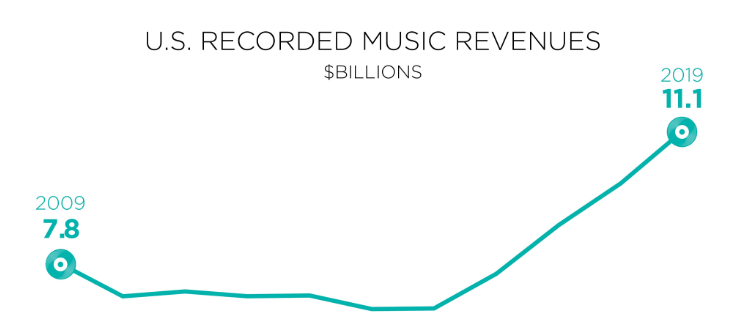

The success of the subscription streaming model for music is perhaps best expressed in this simple chart:

Note that slippery slope from 2009 through to mid-decade, and then ask yourself what happened circa 2015-16 that suddenly not just reversed the decline but sent music revenue to hitherto unheard of heights?

Of course it was Spotify’s, Apple’s and Amazon’s unlimited streaming services (respectively 2011, 2015 and 2016). The slow start when Spotify arrived on the scene reflects initial music publisher resistance, just as we see today with book publishing.

Per TNPS in February 2020,

Streaming music services’ share of total music revenues is bigger than ever. According to a year-end report from the RIAA, revenues from streaming services grew nearly 20% in 2019 to $8.8 billion, accounting for 79.5% of all recorded music revenues.

According to the RIAA, the U.S. streaming market in 2019 was larger than the entire U.S. recorded music market just two years ago.

We see in the Nordics, and especially in Sweden, how, when publishers embrace digital and streaming instead of blocking content and raising à la carte digital prices, that everyone’s a winner.

But the problem is that many publishers outside Sweden do not want to hear this. Better to look the other way and hope consumers at home don’t get any ideas above their station.

Of course publishers will tell us consumers want printed books and the fact that print books outsell ebooks and not many people subscribe to the existing book streaming services like Scribd proves their point.

Which sounds remarkably like the way music companies used to tell us consumers wanted vinyl or CDs, or that film studios insist film-lovers want the expense and inconvenience of heading off to cinemas if they want to see the latest blockbuster while it’s still new.

The reality is consumers want content when they want it, how they want it, and at a price they are comfortable with.

Yes, some music lovers will still pay through the nose for vinyl, and there will always be theatres for those who want that unique cinematic experience and an overpriced hot-dog, a bucket of popcorn and a giant soda.

But music publishers, news publishers and now movie studios have realised that fighting the subscription model is like King Knut trying to hold back the tide.

Book publishers mostly cling to the old model, even as the digital-first publishers reap the rewards. Big Pub will point to Scribd and say, “only 1 million subscribers”. But what we should be asking is how many subscribers would there be is Scribd was allowed the full catalogues of the major publishing houses?

The development of the subscription model is hampered by two factors – Amazon’s dominance of the digital retail and subscription books (Kindle Unlimited) markets, and the reluctance of publishers to feed their most popular titles into the subscription system. In both cases publishers created the situation, and only publishers can resolve the problem.

But where are the book publishers brave enough to put out their front-list content on streaming services or as à la carte digital at appropriate digital prices?

Pricing ebooks as high or higher than the print version, or not putting big-name titles out on streaming services, does not tell us about real consumer demand. It tells us only that publishers are protecting their vested interests in past models.

And at a time when western publishing is trying to shake off its gentleman’s club image and embrace diversity, modernity and reach new audiences, it’s a crying shame that the best way that can be achieved – by taking digital subscription seriously – is still not on the agenda.