Can Spotify dominate the audiobook scene in the same way it has music? No is the simple answer. But it will fundamentally change the audiobook model in the western markets before this decade is over

Despite a move into podcasts, Spotify has thus far studiously avoided the audiobook sector, likely to the relief of those already competing in this field, given Spotify’s dominance of the music streaming world.

With 138 million paying subscribers and 299 million monthly users Spotify is by far the biggest audio platform in the world (for comparison Amazon Music hit 55 million subscribers as this year began), and revenues for the last three quarters to end June 2020 hit $2.25 billion.

Can Spotify dominate the audiobook scene in the same way?

No is the simple answer. But it will fundamentally change the audiobook model in the western markets before this decade is over.

Here’s the thing:

Spotify, founded in 2006 in Sweden and launching in the US in 2011 as it clocked its first million subscribers, is just now advertising for an audiobook supremo for the US, to be based in either New York or Los Angeles. The job description gives us some useful insights as to where Spotify might be going with this:

Spotify Studios is the team that oversees our spoken word content business, including original content. We’re looking for a creative, driven, and experienced executive to join the Spotify Studios team, reporting directly into the Head of New Initiatives / Partnerships.

This is an opportunity to imagine new possibilities for what audiobooks can be.

Digging deeper, we find the job description entails:

• Identifying third-party content to license and package on the Spotify

• Coordinating with our Content Partnership team to establish and manage relationships with the key producers, publishers and licensors

And most significantly:

• Develop, pitch and oversee production of high-quality content

Original content is essential for any subscription service to compete – just ask Audible or Storytel – and while we might think this is uncharted waters for Spotify the company has in fact been focussed on original content for its podcasting arm, and at the end of the day it doesn’t require any special skills on Spotify’s part other than to hire the right people and make the right connections.

And connections come easily to a company of Spotify’s standing. Just last month Michelle Obama joined Spotify’s podcasting portfolio with an exclusive deal. In June it was Kim Kardsahian West signing up. And in May Joe Rogan signed a multi-year deal.

Audiobooks are a different sector, of course, but it’s pretty clear where this is heading, leaving the big question: how will publishers react?

There are two key issues here:

First, Spotify’s move into audiobooks is English-language focussed at this time, and while that’s a big market, it puts the company on collision course with Amazon-owned Audible and also-US-based Scribd, Nook, Apple and Google Play, while barely impacting on Storytel, Nextory, Bookbeat, Audioteka, Ubook and the other key audiobooks players with a more global focus.

It’s a bold move, and begs the question why Spotify, which originated in Sweden, thinks it better to kick off with audiobooks in the US, competing with Audible, rather than Sweden competing with Storytel.

And that leads directly into the second major issue here: that the Anglophone publishing community is notoriously adverse to the unlimited subscription model that prevails outside the US/UK but that rules the roost in the Nordics. Spotify, with its mixed menu of unlimited subscription and free-with-adverts model may face a challenging time getting mainstream English-language publishers on board in sufficient volume to make a go of this.

But Spotify comes to the table with an existing platform of serious scale, and a proven record in podcasts.

The kingmaker will be the big publishers, but it will be consumers that that will be the kingmakers’ kingmaker.

Consider: The only English-language markets Storytel has made a play for thus far are Singapore and India, where it faced no competition from Audible. (Audible India launched a year after Storytel India, while Amazon Singapore has no Audible or Kindle service.)

Storytel’s shifting ambitions are worth noting at this juncture. From 2013 through early 2018 the Storytel international homepage carried links to placeholder Storytel sites for countries yet to materialise as Storytel markets.

Austria, Canada, China, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, Japan, Portugal, Romania, South Africa, Switzerland, UK and USA were on the list, but at some point all those disappeared, from public view at least, including the four English-language markets of the US, UK, Canada and South Africa.

Storytel’s Swedish rival Bookbeat tried a launch in the UK and while the operation is still, well, operational, it really doesn’t move the needle, because UK publishers simply aren’t interested in the unlimited subscription model. For the same reason we can safely assume Storytel has for now set aside its Canada, US and UK ambitions.

South Africa? That’s one to watch, but a topic for another post.

The question is, can Spotify turn Anglophone publishers’ heads the way Scribd, Storytel et al, have failed to do?

My guess is yes, in time, and per the headline, while the ripples won’t be felt for some time, we are witnessing a seismic change in the US publishing scene. An earthquake at sea, barely noticed now, but that will set in motion stormy waves and possibly a tsunami to come.

Let me wind up this post by illustrating that statement with a selection of salient points from two posts from earlier this year here at TNPS:

In January 2020 I said, looking at how Amazon Music is somehow in 35 countries while the Kindle store is only in 14 and Audible in fewer still:

But the wider issues here are a) the indifference of all the big western retailers to the emerging publishing markets, whether subscription or à la carte sales, and b) publisher-imposed territorial restrictions – a historical anachronism from a bygone era when print was the only meaningful option.

In the wider publishing world news-focussed publishers are largely agreed that the future is subscription, and that advertising-based publishing models are on the way out.

Book publishers complacently dismiss such notions.

But that’s to underestimate the flexibility of the subscription models emerging (and) what we are clearly seeing are parallel models emerging, determined primarily by the existing infrastructure.

The big publishers in the mature markets are too ideologically wedded to, and financially invested in, the print-first model to make that leap of faith and embrace digital subscription in a big way.

But in the smaller and emerging markets we are seeing real interest in and demand for a model that lets consumers choose their content without unit-price friction.

Much of the resistance to this comes from publishers who prefer to believe digital subscription is somehow only workable in a handful of markets. But almost every month the subscription operators prove that argument wrong, by expanding into those exact markets deemed unsuitable for subscription. Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, East Europe…

The bottom line is, both video and music streaming show clearly that consumers in these countries welcome the model, and that they have the tech infrastructure in place to make it happen.

Books are not music or video, of course, but nor are they so very different.

And we have to then ask ourselves, is the US (and its satellite English-language market catchment area) really that different from these emerging markets?

Publishers still on the fence about subscription – or worse, still in denial – really need to reconsider their position.

The 2020s will be the decade subscription comes of age. As consumers adapt to subscription as the new normal for content consumption so à la carte retail, and especially non-digital retail, will struggle.

By 2030 the publishing landscape will be as different from today as today is from 2010.

That point was rammed home just a month later, in February of this year.

I said then:

It’s hard to remember now but there was a time, and not so very long ago, when music was a physically delivered product, with vinyl, magnetic tape or a CD the meaningful way for music publishers to make money from consumers.

When digital arrived as a possible alternative medium as this century unfurled (the iPod launched in 2001), and as a meaningful alternative with the arrival of the iPad in 2010 (the latter breathing new life into music video), there were all the usual doomsday predictions that nobody would ever pay for music again, streaming devalued music and artists, piracy would bankrupt studios and artists, the sky was falling…

Well, nothing new there. In publishing we’ve had all the same nonsensical debates, just a few years later than in music.

But with a decade of experience behind us now, has streaming devalued music, destroyed the industry, let the pirates take over, or otherwise caused the sky to fall?

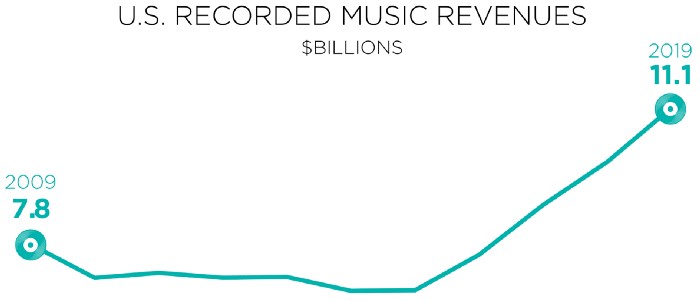

Well, they say a picture is worth a thousand words, so let this graph from Mitch Glazier, Chairman and CEO, RIAA, say it loud and clear.

Note that slippery slope from 2009 through to mid-decade, and then ask yourself what happened that suddenly not just reversed the decline but sent music revenue to hitherto unheard of heights?

Of course it was Spotify’s, Apple’s, Amazon’s and Deezer’s unlimited streaming services (respectively 2011, 2015, 2016 and 2016). The slow start when Spotify arrived on the scene reflects initial music publisher resistance, just as we see today with book publishing.

Put simply, the more players there are, the harder it is for publishers to look the other way. But right now in the US Scribd is the only serious player offering an unlimited audiobook service to consumers.

But let’s return to Mitch Glazier:

Music isn’t “transitioning to digital”– it is leading a digital-first business.

Paid streaming services added an average of more than 1 million new subscriptions per month, as the total number of paid subscribers in the U.S. topped 60 million.

That growth didn’t “just happen.” First and foremost, it requires great music from amazing artists. Over the last decade, record labels have charted a path to new vitality and success by partnering with artists and licensing both established distributors and new start-ups to increase competition and choice.

And therein lies the value subscription brings: increased competition and choice.

In the pre-internet world your choice was only as good as your nearest music shop. Sure, you could order certain singles or albums, if you knew about them – and to know about them usually meant by chance hearing them on a niche radio station – but the reality was most consumers shopped from a small pool of content that bricks & mortar retailers and music publishers chose to offer.

That choice increased as online sales of vinyl, cassettes and CDs proliferated, but still it was a matter of handing over cold hard cash for what might be the only album you could afford that month.

In elementary economics terms, the opportunity was to buy the album you liked most and the opportunity cost was all that other content you couldn’t afford would stay out of your reach, and likely completely unknown.

That’s where subscription changed everything, by offering choice, affordability, and discoverability, and in doing so it fundamentally changed the consumer dynamic.

Music publishers were not instant in grasping the opportunity unfolding, as we see from the graph, but with fierce competition from major services like Spotify, Apple Music, Amazon Music, Deezer, etc, all proving consumers wanted this new model, publisher resistance was futile, and music publishers learned to embrace and exploit the subscription opportunity. With spectacular results.

From TechCrunch:

Streaming music services’ share of total music revenues is bigger than ever. According to a year-end report from the RIAA, revenues from streaming services grew nearly 20% in 2019 to $8.8 billion, accounting for 79.5% of all recorded music revenues.

According to the RIAA, the U.S. streaming market in 2019 was larger than the entire U.S. recorded music market just two years ago.

At which point we have to look back to that Spotify launch in 2011 in the US, and wonder not so much if, as when Spotify Audiobooks will take off.

US and other Anglophone publishers have been complacent so far in handing to Amazon’s Audible the level of control they went on to regret with ebooks. But for how much longer?

Spotify’s consumer-base of proven unlimited-subscription fans is going to turn heads, for sure. Publishers know in their hearts that letting Audible have control of the audiobook market is going to backfire one day.

And they also know that the Audible model of one credit per month subscription has its downsides. Not least that the unlimited subscription model is far more attractive to consumers.

They also know that the unlimited model opens up backlist revenue opportunities like no other.

That’s not so important right now, when publishers are still catching up with audio for their frontlist titles. But the time is not that far off where mature-market publishers are going to look again at the unlimited model, grasp that revenue and profit are not the same thing and that big revenue with less profit isn’t such a great idea, and start switching allegiance. This is business, after all, and money talks.

As Spotify and others grab more “Big Pub” title share so Audible, comfortable now with its credit-subscription model, will simply introduce its own unlimited model to retain its customer-base.

It’s at that point that the ripples from the quake about to happen will finally reach shore.

Make no mistake. The seismic shift is already underway.

I hope to see a big battle between Audible and Spotify. I don’t think that Spotify can dominate the audiobook market but I think it can take a big piece of the pie.

Looking forward to it.

Kind regards

This shouldn’t be shocking at all considering how well-liked Spotify has become as a podcast and music streaming service. They host audiobooks as well, and they have a huge selection of them.

Apple and Spotify have had a long-running feud over Apple’s App Store policies, with numerous public clashes over app and subscription fees.

Interestingly, audio books represent a fairly small segment of readers overall. The latest data from readers themselves ( https://thgmwriters.com/blog/global-book-reading-statistics-2022-2023-complete-survey-data/ ) pins it at about 8%.

Still, that is a huge market. I wonder if Spotify could grow that market by reaching new audiences – “listeners”, as opposed to “readers” – and move the needle up to 10% or beyond.

The expansion of Spotify into the audiobook realm marks a seismic shift in the publishing landscape, undoubtedly. However, while this move promises new avenues for authors and publishers alike, it also underscores the enduring importance of professional book editing services. As audiobooks gain traction, ensuring the highest quality content remains paramount. Professional book editing not only enhances the overall narrative flow and coherence but also maintains the integrity of the author’s voice across different formats. In this evolving landscape, where content consumption is diversifying, the role of skilled editors becomes even more critical in maintaining the standards of storytelling and literary excellence.

The rise of audiobooks marks a seismic shift in the publishing landscape, reshaping how we consume stories and information. While this transformation is still unfolding, the impact is undeniable, and the role of the best audiobook narrators has never been more critical. Their voices bring stories to life, making this new era of publishing a more immersive experience for listeners worldwide.

Spotify’s expansion into audiobooks could open exciting new opportunities for every audiobook narrator big changes are coming, even if the impact isn’t immediate.